Employee Database

title: Employee Database Tutorial

sidebar_label: Basic - Employee Database

This tutorial can be accessed interactively with a Google Colab session here.

You can also download the Jupyter notebook to explore it locally:

Todo: add link to updated Notebook: employee-database.ipynb

Introduction

There are many features of the zef ecosystem to explore but several are core

concepts from which the rest can be understood. This tutorial aims to quickly

demonstrate the core parts of the zef language. At the end, you should

understand:

- How to query a graph, by traversing relations and accessing atomic values.

- Append new information to a graph using the transact and shorthand syntaxes.

- Understand how to use the lazy zef operator syntax.

- Be able to share your graph with others and collaborate.

In particular, these programmatic operations and types will be covered:

GraphZefRefGraphDeltaET,RTOut,In,out_rel,in_rel,Outs,Inscollect,run,for_eachZ["..."]now,value,single,terminate,map,uid,all,frame

Goal

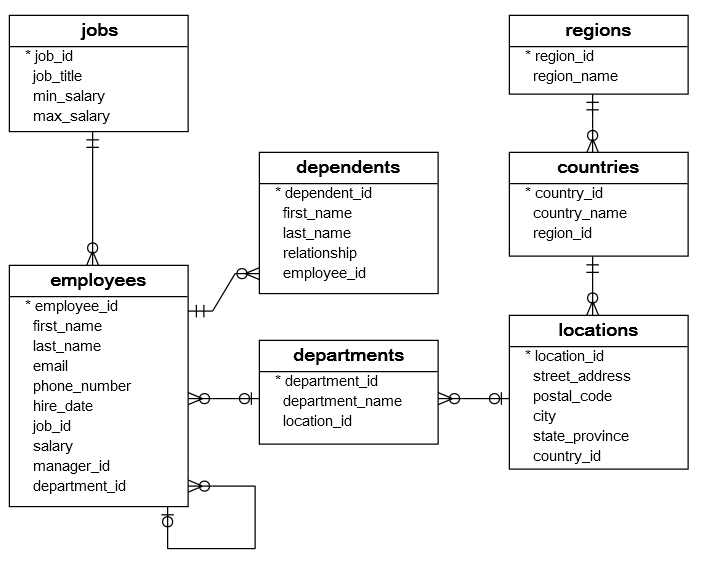

Let's create a database representation of something similar to the relation database shown at https://www.sqltutorial.org/sql-sample-database/.

This information is meant to describe a company's distribution of employees,

jobs and departments. As we are using a graph database, we will not duplicate

this exact structure as it is inflexible. Instead, we will show some of the unique

flexibility of graph databases and zefDB's flat layout. In this tutorial, the

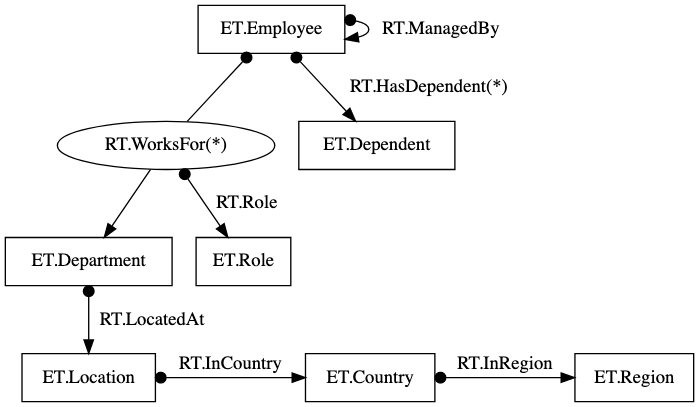

equivalent graph layout to the above relational table layout will be:

where * indicates multiple relations may be present.

Filling in some structure

Firstly, create a blank graph and add to it some entities representing people and departments.

from zef import *

from zef.ops import *

g = Graph()

Creating a graph is done with Graph(). By default, this creates a local graph

which is not synchronized with ZefHub.

z_alice = ET.Employee | g | run

z_bob = ET.Employee | g | run

z_charlie = ET.Employee | g | run

z_alex = ET.Employee | g | run

z_hr = ET.Department | g | run

z_research = ET.Department | g | run

(z_alice, RT.WorksFor, z_research) | g | run

(z_bob, RT.WorksFor, z_hr) | g | run

(z_charlie, RT.WorksFor, z_hr) | g | run

(z_charlie, RT.WorksFor, z_research) | g | run;

The notation <template> | g creates an Effect to append a single fact to the

graph. We run this effect, and the return value is a ZefRef which is a

reference to that created entity or relation. In this list we have two "types"

which are an entity type ET and a relation type RT. You can think of these

as nearly equivalent to a string naming the type.

z_alice

<ZefRef #97 ET.Employee slice=2>

z_hr

<ZefRef #171 ET.Department slice=6>

An ET.Something or RT.Something will add a new type or reuse an existing

type. Under the hood, these are tokenized to integers for optimized accesses and

are consistent across different graphs.

Don't be afraid to create new types. As you add new types, they will be added to

your user namespace, and can be later "forgotten" if you would like to clean up

your namespace.

A key difference here to a relational database is that the employee can have

multiple relations to different departments, a feature which typically requires

multiple table rows in a relational database. In the above, Charlie can work for

both the HR and Research departments. In contrast, Alex works for no department

(maybe they are a new hire or an intern).

The input of the data above is a little clumsy and verbose. We could compress many of the elements into fewer templates:

g = Graph()

[z_alice,z_bob,z_charlie,z_alex,

z_hr,z_research] = [ET.Employee, ET.Employee, ET.Employee, ET.Employee,

ET.Department, ET.Department] | g | run

(z_alice, RT.WorksFor, z_research) | g | run

(z_bob, RT.WorksFor, z_hr) | g | run

(z_charlie, RT.WorksFor, [z_hr, z_research]) | g | run;

In the first line, a template consisting of 4 ET.Employees and 2

ET.Departments requests that 6 new entities be created. The return value is

then "unpacked" into 6 different variables. The final line of code creates two

relations from z_charlie to z_hr and z_research.

Even with the compressed syntax there are a couple of problems:

- it looks confusing

- multiple database transactions are caused by each

... | g | run.

Instead, we can use the transact operator:

g = Graph()

receipt = [

ET.Employee["alice"],

ET.Employee["bob"],

ET.Employee["charlie"],

ET.Employee["alex"],

(Z["alice"], RT.WorksFor, Z["research"]),

(Z["bob"], RT.WorksFor, Z["hr"]),

(Z["charlie"], RT.WorksFor, Z["hr"]),

(Z["charlie"], RT.WorksFor, Z["research"]),

ET.Department["hr"],

ET.Department["research"],

] | transact[g] | run

z_alice = receipt["alice"]

z_bob = receipt["bob"]

z_charlie = receipt["charlie"]

z_alex = receipt["alex"]

z_hr = receipt["hr"]

z_research = receipt["research"]

Here, each item in the list passed to the GraphDelta is one fact to be added

to the database, but all will be done in the one transaction. There are two

kinds of facts shown here:

- a new entity (e.g.

ET.Employee) and - a new relation

(a, RT.Something, c).

To connect the facts together, each entity/relation can be given an internal (and temporary) name. A string following an ET or RT sets this internal name (e.g. ET.Employee["alice"]) and the special object Z can be used to reference this name (e.g. Z["alice"]).

After the GraphDelta has been run on the graph, a "receipt" is returned which allows access to the created

entities and relations via their internal names.

The order is also not important - for example, the fact describing the relation

between Z["alice"] and Z["research"] is given before the name "research"

is known (in ET.Department["research"]). You can use this to organise the

transact as makes sense in your particular context.

One can think of the Z["name"] notation as similar to using a variable called

name. Because a transact uses a declaritive style (that is, it

declares the facts to create) rather than an imperative style (which would list

a series of actions to perform in a specific order) variables are not necessary.

For example, the transact

reciept = [

ET.Employee["alice"],

(Z["alice"], RT.WorksFor, Z["research"]),

ET.Department["research"]

] | transact[g] | run

z_alice = receipt["alice"]

z_research = receipt["research"]

could be re-imagined in an imperative style with the pseudo-code (notice the

analogy between Z["alice"] and alice:

alice = create_entiy(ET.Employee)

research = create_entity(ET.Research)

link_entities_by_relation(alice, RT.Department, research)

Note this pseudo-code does not work and the functions create_entity and

link_entities_by_relation do not exist!

Attaching some details

The above was only the high-level structure between some employees and some

departments. We didn't need to specify exactly what an ET.Employee

entity is, or what properties it might have. In fact, in zefDB there is no such

concept of a "property" of an entity. Instead, we use a flat representation to

attach other details. For example:

[

(z_alice, RT.FirstName, "Alice"),

(z_alice, RT.LastName, "Smith"),

(z_alice, RT.Email, "alice.smith@invalid.address"),

(z_alice, RT.Email, "alice.smith52@backup.address"),

(z_alice, RT.HireDate, Time("2022-01-11")),

(z_alice, RT.Salary, QuantityFloat(73100.0, EN.Unit.AUD)),

(z_bob, RT.FirstName, "Bob"),

# ...

(z_charlie, RT.FirstName, "Charlie"),

# ...

(z_alex, RT.FirstName, "Alex"),

# ...

(z_hr, RT.Name, "HR"),

# ...

(z_research, RT.Name, "Research"),

# ...

] | transact[g] | run;

We have shown a variety of types available for values. It is possible assign

String, Int, Float, Time, QuantityFloat, QuantityInt to what are

known as "atomic entities". In contrast, entities only have an identity but

never a value. To show the current state of z_alice use the yo op:

yo(now(z_alice)) # option 1

z_alice | now | yo | collect # option 2

You should see something like

================================================== Historical View ==================================================

===================================== Seen from: 3: 2022-01-12 12:36:28 (+0800) =================================

<...snip...>

1x: (z:ET.Employee) -------------------------(RT.WorksFor)-----------------------> (ET.Department)

(z) ----(603d3be2b5ba277a48cc05798023a1df)---> (264a2177d0a36cce48cc05798023a1df)

1x: (z:ET.Employee) ------------------------(RT.FirstName)-----------------------> (AET.String)

(z) ----(8e6809d8f232af7b48cc05798023a1df)---> (72f79ec427603a7448cc05798023a1df [latest val: Alice])

<...snip...>

1x: (z:ET.Employee) -------------------------(RT.HireDate)-----------------------> (AET.Time)

(z) ----(93b8c0bdc806fd6548cc05798023a1df)---> (21157012f1e9d0ad48cc05798023a1df [latest val: 2022-01-11 00:00:00 (+0800)])

1x: (z:ET.Employee) --------------------------(RT.Salary)------------------------> (AET.QuantityFloat.AUD)

(z) ----(061547c736a45a2648cc05798023a1df)---> (6bd9b5b7b42ea9bb48cc05798023a1df [latest val: <QuantityFloat: 73100 EN.Unit.AUD>])

<...snip...>

Alice is an employee with many relations heading outwards from the entity. These

are all "at the same level", i.e. flat. The relation connecting Alice to the

research department entity (of type ET.Department) is at the same level as the

relation connecting Alice to the atomic entity containing her first name "Alice"

(of type AET.String).

If you simply ask for yo(z_alice) (try this) you will not see all of the above

information. That's because each ZefRef is simply a pair of (identity, reference_frame) and z_alice was returned from a reference frame when the

entity was first created, before any of Alice's properties were attached. This should be noticable in the

header of the yo output above, where the second line shows "Seen from 3". This

emphasizes that the "time slice" (here 3) the information about the entity is

shown from may be in the past.

Compared with the SQL table definition, Alice is missing several columns:

employee_id: this is not needed as every entity on the graph has a unique ID already (tryuid(z_alice))phone_number: we chose to not provide a phone number, which is valid on a graph. A relation database might choose to use a sentinel value to indicate a missing phone number instead.department_id: instead of indirectly connecting the employee to a department, we have directly linked the employee using a relation.email: we have provided two email addresses for Alice. This is easy to do in a graph database but requires much forethought in a relational database.

Each line in the GraphDelta that added one property (e.g. (z_alice, RT.FirstName, "Alice")) is a shorthand for several elementary operations. The same effect could be obtained via:

ae = AET.String | g | run # Create the atomic entity without a value

ae | assign_value["Alice"] | run # Assign a value to the atomic entity

(z_alice, RT.FirstName, ae) | g | run # Connect the atomic entity to z_alice

# ... the above is the same as ...

(z_alice, RT.FirstName, "Alice") | g | run

Injecting some elegance

While the underlying layout on the graph might be flat, we often think about data in a tree-like manner. So there is another option to provide the information for an entity:

{z_bob: {

#RT.FirstName: "Bob", # This is commented out to prevent adding a RT.FirstName twice.

RT.LastName: "Jones",

RT.Email: "bob.jones@invalid.address",

RT.HireDate: Time("2022-01-12"),

RT.Salary: QuantityFloat(100.0, EN.Unit.AUD)

}} | g | run;

Querying the data

If we did not know Alice's name and wanted to obtain this from the ZefRef of z_alice, then we could write the following:

first_name_ae = z_alice | now | Out[RT.FirstName] | collect

name_string = first_name_ae | value | collect

# ... or ...

name_string = z_alice | now | Out[RT.FirstName] | value | collect

name_string

'Alice'

Here, the operation Out says to "traverse the prior ZefRef along the

following outgoing relation", that is RT.FirstName. The output of this is

itself another ZefRef. There is an equivalent operation In for traversing

along an incoming relation, hence:

z_alice | now | Out[RT.FirstName] | In[RT.FirstName] | collect == now(z_alice)

True

Finally, once we have the ZefRef to the atomic value containing

the name, we grab the value itself using the op value.

You might be wondering what the | collect operations are for, and why there

seem to be | characters everywhere. This is due to the lazy evaluation

features of zefDB. If we write

z_alice | now

LazyValue(<ZefRef #187 ET.Employee slice=2> | now)

or

z_alice >> RT.FirstName

LazyValue(<ZefRef #187 ET.Employee slice=2> | out_out_old[RT.FirstName])

we obtain an object of type LazyValue instead of a ZefRef that we might

expect. This allows for the composition of expressions without evaluation,

useful for functional design and an essential aspect of distributed queries and

computing. To cause evaluation, we can pass this LazyValue through a

collect.

For named operations, like now and value, we can cause immediate evaluation

using the function call syntax:

value(now(z_alice) | Out[RT.FirstName]) == z_alice | now | Out[RT.FirstName] | value | collect

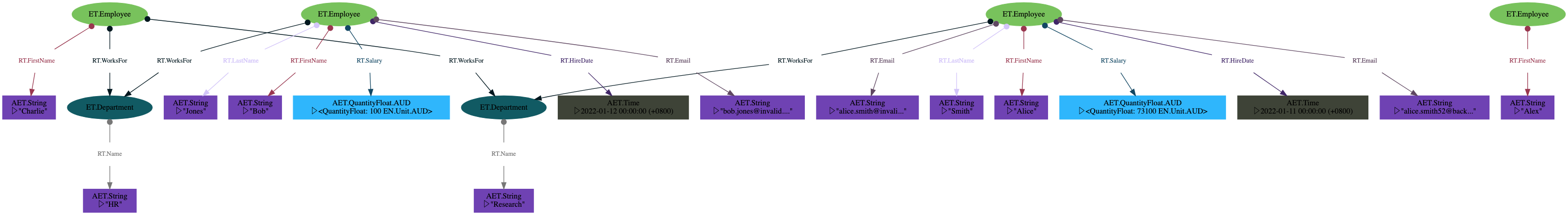

To obtain a quick visualisation of the current graph layout, we can use the

graphviz operator. This requires both the program

graphviz and the python packagegraphviz to be installed. Then you can

simply run:

# Make sure both the graphviz program and the python package graphviz are

# installed before running this command.

g | now | all | graphviz | collect

This will autogenerate a visualisation with a layout that will likely require

some zooming to view all of the individual parts.

Note: the graphviz return type is an Image which is automatically displayed in Jupyter. At the REPL you should instead, for example, run save this to a variable viz and run viz.view().

Exploiting relations

Relations in all graph databases can connect entities, that is, a relation can begin or

end at an entity. In Zef graphs, relations are also allowed to begin or end at a

relation. This is very helpful to represent facts which are connected to a pair

of entities. For example, if an employee is associated with multiple

departments, like "Charlie" in our example above, we might want to attach

additional facts that describe what role or what fraction of time Charlie

spends in the HR and Research departments. This might be better explained by

example, creating a new employee:

# We create a new employee to show how everything can be added in one step

receipt = [

{ET.Employee["zaphod"]: {

RT.FirstName: "Zaphod",

RT.LastName: "Beeblebrox",

}},

(Z["zaphod"], RT.WorksFor["zaphod-hr"], z_hr),

(Z["zaphod"], RT.WorksFor["zaphod-research"], z_research),

{Z["zaphod-hr"]: {

RT.Role: "busy body",

RT.Fraction: 0.1,

}},

{Z["zaphod-research"]: {

RT.Role: "general nuisance",

RT.Fraction: 0.9,

}},

] | transact[g] | run

z_zaphod = receipt["zaphod"]

Notice that we can assign internal names to the RT.WorksFor relations and this

is one method to create relations out of relations. Alternatively, we can first

obtain a relation using the relation operator.

z_charlie_hr = relation(now(z_charlie), now(z_hr))

z_charlie_research = relation(now(z_charlie), now(z_research))

[

(z_charlie_hr, RT.Role, "Recruitment"),

(z_charlie_research, RT.Role, "Manager"),

] | transact[g] | run;

For Zaphod, we included a RT.Fraction but this was left off of Charlie's details. The lack of a RT.Fraction needs to be understood in the graph context.

It could be interpreted as:

- Charlie spends equal time in all roles, or

- Charlie provides floating support, or

- the data is incomplete and represents an error in the data

Exactly which of these interpretations apply would

be part of the data model.

If we wish to remove a fact from the database, we can terminate it:

z_zaphod | terminate | g | run

# Alternatively...

# [terminate(z_zaphod)] | transact[g] | run

<ZefRef #931 ET.Employee slice=7>

Terminating an entity such as z_zaphod will also terminate any relations that

were pointing to it. Hence, the RT.WorksFor relation connecting z_zaphod to

z_hr was also terminated, along with the RT.Role in turn.

Knowing when to place facts on a relation between two entities, as opposed to

one of the entities directly can often be determined by what behavior would be

expected by terminate. For example, the RT.Role fact would become

meaningless if either of z_zaphod or z_hr were removed, hence placing it on

the connecting relation makes sense.

In contrast, a hire date associated with Zaphod makes more sense to be attached

directly to z_zaphod, even though it might also be the same time as when

Zaphod started in the HR department. If the department entity were terminated,

then it would be incorrect to also remove the hire date of Zaphod.

Queries out of nothing

So far, we have created items on the graph, and then accessed them using the

ZefRef that was returned from the creation effect. If we instead approach the

graph without any prior references, we need to be able to access these

previously stored facts.

A Zef query is not formulated like an SQL query. We can directly interact with a

graph, and programmatically apply filtering, traversals and transformations.

Here is how we could obtain all employee entities, and print their IDs and first

names:

employees = g | now | all[ET.Employee] | collect

# Using zef ops

make_output = lambda z: (uid(z), value(z | Out[RT.FirstName]))

employees | map[make_output] | for_each[unpack[print]]

# Using traditional python

for z in employees:

print(*make_output(z))

b501be56d899f77e931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Alex

820a3434a983e82e931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Charlie

e792dc1ab793b393931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Bob

21bd50c7b8ddd159931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Alice

b501be56d899f77e931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Alex

820a3434a983e82e931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Charlie

e792dc1ab793b393931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Bob

21bd50c7b8ddd159931b00e1e97a4f5c53bdc9821d767ec8 Alice

employees is a list holding a bunch of ZefRefs.

Notice that there should be no "Zaphod" in the list, as this node was

terminated. However, zefDB is an append-only database with time travel built in,

so it is possible to go back and view the facts of the graph at an earlier time:

# This code assumes z_zaphod is the same variable as would have been created

# from the code earlier in this tutorial.

employees = z_zaphod | frame | all[ET.Employee] | collect

employees | map[make_output] | for_each[unpack[print]];

b501be56d899f77e5888ae8da8d112ef53bdc9821d767ec8 Alex

820a3434a983e82e5888ae8da8d112ef53bdc9821d767ec8 Charlie

e792dc1ab793b3935888ae8da8d112ef53bdc9821d767ec8 Bob

21bd50c7b8ddd1595888ae8da8d112ef53bdc9821d767ec8 Alice

aae05777c02978bc5888ae8da8d112ef53bdc9821d767ec8 Zaphod

Here, we use the op frame to get the reference frame of z_zaphod, which is the frame

in which the ET.Employee for Zaphod was created. We then ask for all

ET.Employee in the context of this reference frame.

It is also possible ask for all employees that ever existed:

# First create a new employee:

z_trillian,_,_ = (ET.Employee, RT.FirstName, "Trillian") | g | run

employees = g | all[ET.Employee] | collect

# Note: as the employees have no reference frame, we need to

# pass in one to `value` to allow it to return something sensible.

employees | map[lambda z: (uid(z), z | Out[RT.FirstName] | value[now(g)] | collect)] | for_each[unpack[print]];

b501be56d899f77e53bdc9821d767ec8 Alex

820a3434a983e82e53bdc9821d767ec8 Charlie

e792dc1ab793b39353bdc9821d767ec8 Bob

21bd50c7b8ddd15953bdc9821d767ec8 Alice

aae05777c02978bc53bdc9821d767ec8 Zaphod

d974cebb8e1d2d6853bdc9821d767ec8 Trillian

Here, we simply ask for all ET.Employee of the graph, which not a reference

frame, in contrast to g | now | all[...]. We see all employees, including both

"Zaphod" and "Trillian" despite there never being a single time in which both

were employeed (remember the order, the Zaphod entity was created, then

terminated, then the Trillian entity was created).

Objects returned from a reference frame are ZefRefs which are effectively a

(identity, reference_frame) pair. The objects returned by g | all[...] are

EZefRefs ("eternal ZefRefs"), which are the identity alone. More discussion

on the differences between a ZefRef and EZefRef can be found here(todo).

To ask for a particular employee we can filter on these results. For example:

z_found = (g | now | all[ET.Employee]

| filter[Out[RT.FirstName]

| value

| equals["Alice"]]

| single

| collect)

The filter op filters a list based on the predicate function/op curried into

it. Note that Z >> RT.FirstName is effectively the same as lambda z: z >> RT.FirstName. Finally, the single op takes a list of a single element and

returns that element. If the list is empty, or contains two or more elements, it

would raise an error.

As this is programmatic, we can now continue to use the ZefRef result in

z_found to query the graph:

print(f"The employee {value(z_found | Out[RT.FirstName])} {value(z_found | Out[RT.LastName])} was hired on {value(z_found | Out[RT.HireDate])}")

The employee Alice Smith was hired on 2022-01-11 00:00:00 (+0800)

Complex queries

In SQL, joins between multiple tables are necessary to perform interesting

queries. In graph databases, we instead traverse relations. We have already seen

how we can traverse a single relation with z_zaphod | Out[RT.FirstName]. We can

also traverse multiple relations:

names = z_hr | now | Ins[RT.WorksFor] | map[Out[RT.FirstName] | value] | collect

print(names)

['Charlie', 'Bob']

Here, z | Ins[RT.WorksFor] asks for all sources of RT.WorksFor relations

incoming to z. It will always return a list, even if there is only a single

relation, hence z | In[RT.WorksFor] is equivalent to z | Ins[RT.WorksFor] | single.

Finally, we have seen how to attach facts to relations, by allowing relations to

start from other relations. To query for this we use out_rel and in_rel which are

analogous to Out and In:

roles = z_charlie | now | out_rels[RT.WorksFor] | map[Out[RT.Role] | value] | collect

print(roles)

['Manager', 'Recruitment']

The out_rels[RT.WorksFor] returns a list of the relations outgoing from the

entity, instead of their targets, as would be returned by Outs[RT.WorksFor]. In fact, we can say that z | Outs[RT.Something] == z | out_rels[RT.Something] | map[target]. An alternative way to describe this is "Out and In follow

relations to one of their end, whereas out_rel and in_rel stop on the relation".

Labelling composite queries

Most of the time, we would like to reuse queries. As these are lazy operations,

this as simple as assigning them to a variable:

get_roles_simple = now | out_rels[RT.WorksFor] | map[Out[RT.Role] | value]

get_roles = (Assert[is_a[ET.Employee]]

| now

| out_rels[RT.WorksFor]

| map[Outs[RT.Role] | single_or[None]] # Follow RT.Role if it exists, otherwise return None

| map[value_or["<missing role name>"]]) # Get the value, but if None return "<missing role name>"

z_charlie | get_roles | collect | run[print]

z_alice | get_roles | collect | run[print]

['Manager', 'Recruitment']

['<missing role name>']

The get_roles_simple form is nearly identical to what we wrote before. The

more complex form underneath also includes an assertion (which will complain if

the ZefRef passed in is not an ET.Employee) and proper handling for the case

that a RT.Role is missing. This zefop can now be used more concisely in

interesting cases:

all_roles = (g | now | all[ET.Employee]

| map[get_roles | collect]

| concat

| distinct

| collect)

print(all_roles)

['Manager', 'Recruitment', '<missing role name>']

Note that we can also write a python function to implement get_roles and

decorate it so that it can be used like an op:

@func

def get_roles2(z):

assert is_a(z, ET.Employee)

rels = z | now | out_rels[RT.WorksFor]

roles = []

g = Graph(z)

for rel in rels:

if rel | has_out[RT.Role] | collect:

role = rel | Out[RT.Role] | value | collect

else:

role = "<missing role name>"

roles.append(role)

return roles

z_charlie | get_roles2 | collect | run[print]

z_alice | get_roles2 | collect | run[print]

['Manager', 'Recruitment']

['<missing role name>']

A function decorated with @func can also be permanently attached to a graph

via the @func(g) syntax. See here(todo) for more detail.

Persisting data for later use

Although we have left this for last, it is actually one of the simplest steps in

this tutorial. If you would like to save the graph you are working on to be able

to return to it in the future, then simply call:

g | sync | run

g | tag["employee-records"] | run

This will indicate you would like to synchronize this graph on ZefHub. The

default graph permissions are private to your user. To access the graph in the

future you can simply pass this tag as the requested graph:

g = Graph("employee-records")

The above has associated the graph you created with the tag your-user-name/employee-records. If you try and tag a new graph (e.g. by running this notebook again) then an error will appear, saying that a graph is already tagged.

If you want to put a tag on a new graph you should either:

Graph("employee-records") | untag["employee-records"] | run

or

g | tag["employee-records"][True] | run

where the True means "steal tag from my other graph".

To share your graph with others, you can give them permissions to

view/append/host the graph:

"user.name@email.com" | grant[KW.view][g] | run

"best.friend@email.com" | grant[KW.view][g] | run

"best.friend@email.com" | grant[KW.append][g] | run

These users can then access the graph via Graph("employee-records"). To remove

privileges, the revoke op is similarly available.

But wait!

Eagle-eyed readers would have noticed a difference between the code in this

tutorial and the initial layout image. In particular, instead of a RT.Role

relation connecting a RT.WorksFor relation with an ET.Role, the RT.Role in

the actual code we used simply pointed at a string.

We won't dive into this for now and leave it for another tutorial.